DA88 – Thiên Đường Cá Cược Thể Thao Uy Tín Hàng Đầu 2025

DA88 liên tục lọt vào top nhà cái uy tín đang hoạt động tại thị trường Việt Nam. Sở hữu những thế mạnh nổi bật và tự tin khẳng định thương hiệu lớn mạnh. Người chơi sẽ có được trải nghiệm cá cược hấp dẫn, công bằng, an toàn khi tin tưởng trang web cá cược xanh chín. Anh em hãy cùng chúng tôi khám phá thông tin về nhà cái chất lượng này nhé!

Tổng quan về nhà cái DA88 số 1 Việt Nam

DA88 là nhà cái thể thao trực tuyến được thành lập 2016 tại Manila Philippines, được tổ chức Curacao quản lý và hoạt động theo giấy phép của nhà phát hành trò chơi giải trí trực tuyến. Hiện tại, DA88 đang là đối tác đáng tin cậy của nhà cung cấp game uy tín hàng đầu trên thị trường như GS-Sports, SABA Sports, Evolution, EBet, Ezugi, Pragmatic. Bên cạnh đó, DA88 còn thúc đẩy hoạt động tài trợ cho các đội bóng hàng đầu châu Âu nhằm mở rộng thương hiệu, nâng cao khả năng kết nối với người chơi.

DA88 ra đời với sứ mệnh rõ ràng, hoạt động với mong muốn mang đến sự hài lòng cho khách hàng với 3 tiêu chí:

- Đặt quyền lợi và trải nghiệm của người chơi lên hàng đầu.

- Mang đến trải nghiệm cá cược công bằng.

- Không ngừng đổi mới, phát triển sản phẩm dịch vụ mỗi ngày.

Vì sao người chơi nên chọn DA88 là nhà cái cá cược uy tín?

DA88 là nhà cái cá cược hàng đầu tại Việt Nam. Người chơi đến với nhà cái nhờ vào ưu điểm nổi bật như:

Pháp lý vững chắc và cá cược an toàn

DA được Curacao chứng nhận với giấy phép kinh doanh rõ ràng ngay từ những ngày đầu ra mắt. Chứng chỉ được cấp từ Curacao khẳng định được tên tuổi lớn mạnh của nhà cái và đảm bảo 5 yếu tố chất lượng:

- Kho game đồ sộ, đón đầu xu hướng và đạt chất lượng tốt nhất.

- Dịch vụ CSKH chuyên nghiệp, túc trực 24/7, nhân viên giải đáp thắc mắc của người chơi với thái độ nhiệt tình, niềm nở.

- Hệ thống bảo mật hiện đại, tân tiến, chuẩn SSL 128 bit. Thông tin người chơi luôn được giữ kín tuyệt đối, cam kết không rò rỉ cho bên thứ 3.

- Giao dịch nạp rút tiền nhanh chóng, thao tác đơn giản, thành công chỉ sau 1 – 5 phút.

- DA88 tạo không gian cá cược lành mạnh, nói không với lừa đảo, gian lận.

Đột phá công nghệ đón đầu xu hướng

Hoà mình vào thời đại công nghệ số, DA88 ưu tiên vào đột phá công nghệ hiện đại. Điều này được thể hiện thông qua 4 yếu tố như sau:

- Thanh toán bằng mã QR, thao tác hoàn tất sau 1 phút.

- Ứng dụng di động được tung ra tương thích với Android/iOS và tích hợp tính năng quan trọng, tối ưu giao diện thông minh.

- Đảm bảo về vấn đề trường truyền, mang đến cho người chơi trải nghiệm cá cược mượt, không giật lag.

Quan tâm đến trải nghiệm của mỗi thành viên

Sự hài lòng của thành viên là thành công lớn nhất của DA88. Nhà cái quan tâm đến trải nghiệm của người chơi từ khâu đăng ký tài khoản, tham gia cá cược cho đến nhận thưởng khuyến mãi, giải đáp thắc mắc trên trang web.

Quyền lợi của hội viên luôn là ưu tiên hàng đầu của DA88. Người chơi sẽ được khám phá kho game đồ sộ, tận hưởng trọn vẹn ưu đãi từ hệ thống. Chúng tôi thiết lập hồ sơ cá nhân trên trang web, anh em toàn quyền truy cập để thay đổi, chỉnh sửa dữ liệu theo nhu cầu.

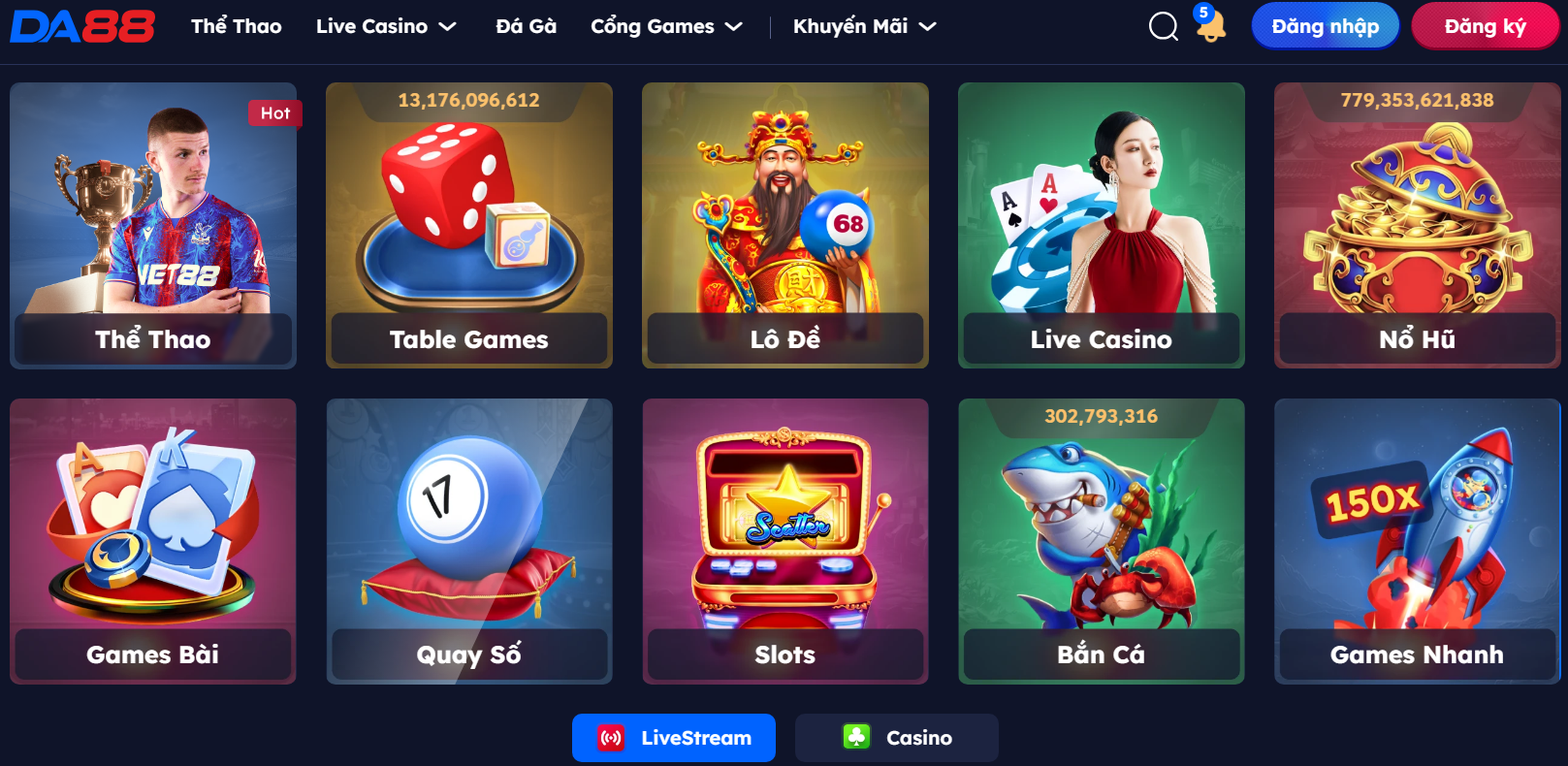

Top game cá cược hấp dẫn trên DA88

DA88 cố gắng nỗ lực để mang đến cho người chơi trải nghiệm cá cược tuyệt vời. Đó là lý do chúng tôi đầu tư vào kho game chất lượng, đa dạng thể loại. Đến với DA88, bet thủ được hoà mình vào danh mục giải trí ấn tượng như:

Thể thao DA88 nóng cùng Euro 2024

Thể thao DA88 là thế mạnh lớn nhất của nhà cái. Tại đây, người chơi chọn cho mình những sảnh cược hấp dẫn gồm: A-Sports, P-Sports, i-Sports, T-Sports, K-Sports. Chúng tôi cung cấp bảng kèo bóng đá, bóng rổ, bóng chuyền, cầu lông, quần vợt và hỗ trợ người chơi đặt cược nhận thưởng minh bạch.

Live Casino DA88 giải trí cùng Dealer nóng bỏng

Điểm nhấn khi chơi cá cược live casino tại DA88 đó chính là bàn cược live trực tiếp và có sự xuất hiện của Dealer người thật. Bet thủ được lựa chọn giải trí tại các sảnh cược nổi tiếng Ebet, Ezugi, PP, MG, Sexy,… Bên cạnh đó là hệ thống game đặc sắc gồm baccarat, roulette, rồng hổ, fantan, xóc đĩa.

Cổng game quy tụ siêu phẩm bậc nhất

Danh mục cổng game quy tụ những cao thủ lão làng. Truy cập tại đây, người chơi thoả sức trải nghiệm giải trí sang trọng và tận hưởng giây phút thư giãn tuyệt vời. Một số sản phẩm đang được săn đón phải kể đến như:

- Nổ hũ: Người chơi săn hũ với hơn 1000+ trò chơi hấp dẫn. Ngoài tiền thưởng, bet thủ còn có thể săn jackpot tiền tỷ cực đã.

- Game bài: Cơ hội đối kháng với cao thủ lão làng trên bàn chơi bài kinh điển như mậu binh, tiến lên đếm lá, phỏm, xì dách, liêng.

- Lô đề: Với những bạc thủ đam mê cá cược lô đề trực tuyến thì hãy đến với DA88. Chúng tôi hỗ trợ anh em đặt cược cực đã với những loại hình gồm: Lô đề 3 miền, siêu tốc, big keno, keno,…

- Bắn cá: Anh em săn cá, tiêu diệt sinh vật biển và nhận xu thưởng hấp dẫn tương ứng vào tài khoản. Một số game bắn cá đón đầu xu hướng xứng đáng để bet thủ trải nghiệm như vua săn cá, đại chiến B52, tỷ phú đại dương, đại hải trình,…

- Game nhanh: DA88 dành thời gian nghiên cứu thị trường và nắm bắt xu thế thời đại. Chúng tôi tích hợp danh mục game nhanh với các siêu phẩm phi công tài ba, dò mìn, aviator, thả bóng ăn tiền đình đám.

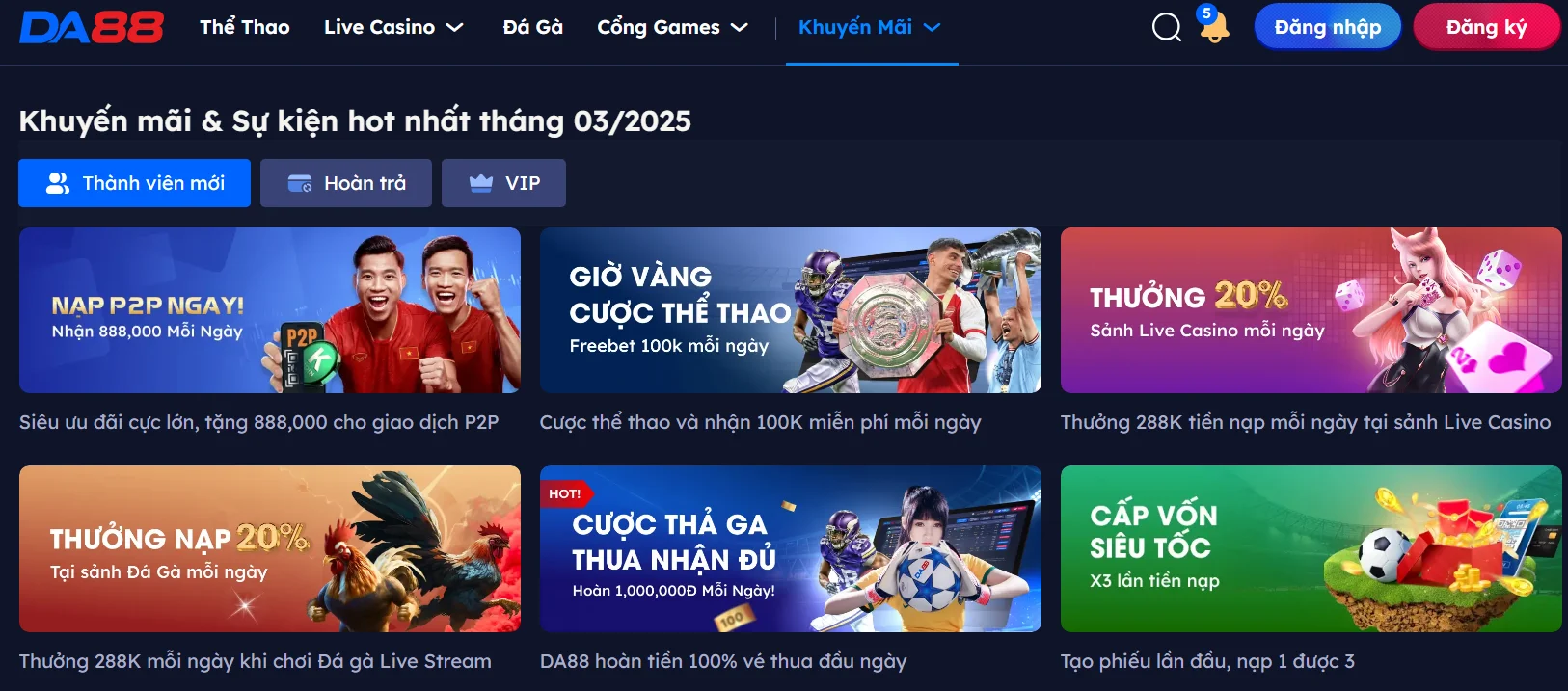

Giải trí ăn thưởng cùng chương trình khuyến mãi DA88 độc quyền

Một trong những lý do DA88 có thể thành công thu hút được đông đảo thành viên sau một thời gian ngắn đó chính là chương trình khuyến hấp dẫn. Ưu đãi độc quyền của DA88 mang đến cho hội viên những khoản tiền thưởng giá trị như:

- Giờ vàng Euro, thưởng 100K mỗi ngày siêu hot.

- Sôi động cùng Copa America, tặng mỗi buổi sáng 100K.

- Vé thua đầu ngày, anh em sẽ được DA88 hoàn tiền 100%.

- Cấp vốn tiêu tốc, nhận gấp 3 lần tiền nạp siêu đỉnh.

- Mỗi thứ 7 hàng tuần, vui vẻ nhận ngay 5.000.000 VND.

- Tặng vốn khởi nghiệp siêu hời lên đến 10.000.000 VND cùng hàng loạt khuyến mãi hấp dẫn đang chờ bạn khám phá.

Hướng dẫn tham gia cá cược cực vui tại DA88

Anh em muốn chơi tại DA88, thuần thục những thao tác cơ bản là yếu tố quan trọng, do đó hướng dẫn được cập nhật dưới đây sẽ rất hữu ích cho bạn!

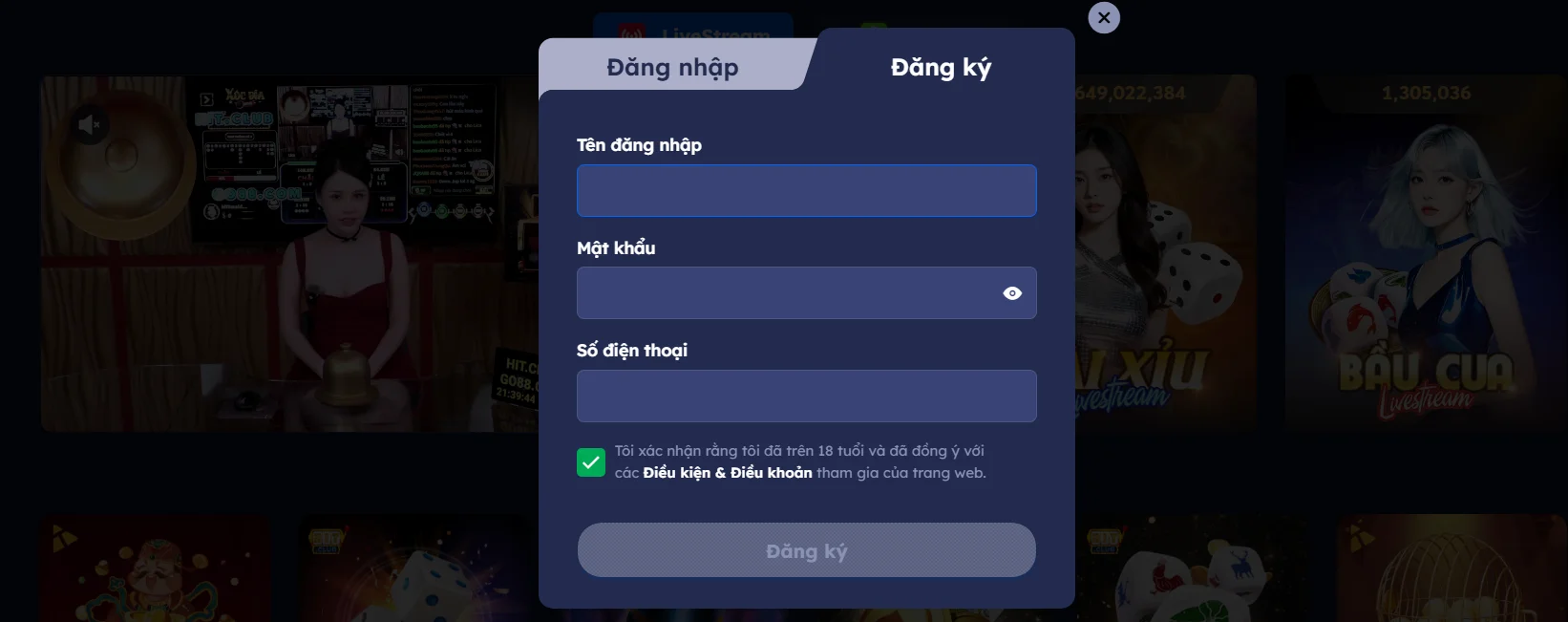

Đăng ký DA88 rinh thưởng khuyến mãi mỏi tay

Thao tác đăng ký DA88 được thực hiện với những bước đơn giản, thành công 100% từ lần đầu tiên thực hiện. Bao gồm:

- Bước 1: Chọn link DA88 uy tín, truy cập trang chủ và chọn Đăng ký, siêu đơn giản.

- Bước 2: Biểu mẫu thiết lập tài khoản hiển thị, người chơi cung cấp thông tin nhanh gọn lẹ như: Tên đăng nhập, mật khẩu, số điện thoại chính chủ.

- Bước 3: Đồng ý với chính sách thành viên, xác nhận đủ từ 18 tuổi trở lên và xác nhận Đăng ký để hoàn tất là tuyệt vời!

P/S: Sau khi đăng ký thành công thì ở lần đăng nhập thứ 2, anh em chỉ cần nhấn chọn vào mục Đăng nhập và điền thông tin theo yêu cầu. Hệ thống sẽ lập tức di chuyển bạn đến giao diện chính thức của nhà cái để tham gia giải trí ăn tiền hấp dẫn.

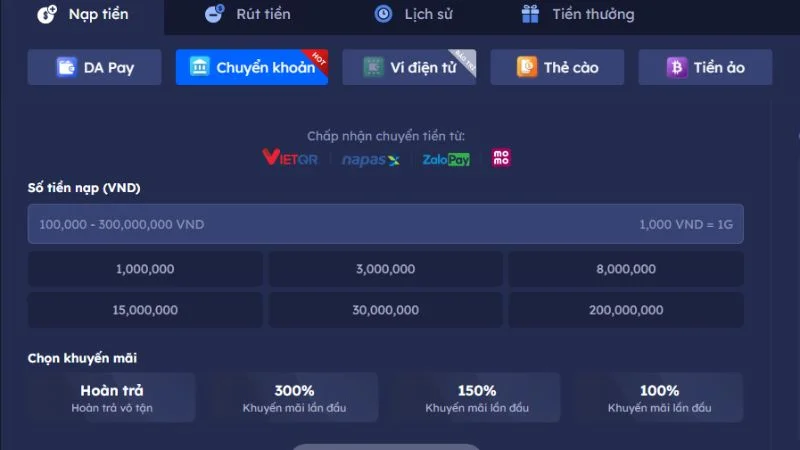

Nạp tiền DA88 nhanh chóng, dễ dàng

Muốn tham gia cá cược trên DA88, người chơi cần có nguồn vốn hợp lệ. Vì vậy, chúng tôi cập nhật hướng dẫn nạp tiền cực dễ, làm theo là chính xác 100%.

- Bước 1: Đăng nhập vào tài khoản DA88, anh em nhấp vào mục Nạp tiền.

- Bước 2: Điền tài khoản ngân hàng bằng cách cung cấp thông tin gồm Ngân hàng, Tên chủ thẻ, Số tài khoản, quá đơn giản!

- Bước 3: Danh sách kênh thanh toán được sân chơi hỗ trợ một cách tuyệt vời như DA Pay, chuyển khoản, ví điện tử, thẻ cào, tiền ảo. Anh em chọn cho mình phương thức phù hợp, nhập số tiền cần nạp, chọn khuyến mãi yêu thích!

- Bước 4: Hoàn tất giao dịch theo thông tin được cung cấp và xác nhận hoàn tất là xong, rất dễ và nhanh!

Tham gia cá cược xanh chín, minh bạch

Sau khi đã nạp tiền hoàn tất, anh em trở về giao diện và thao tác cực nhanh theo hướng dẫn:

- Bước 1: Chọn danh mục giải trí yêu thích để tham gia giải trí cực vui: Thể thao, casino, bắn cá, lô đề, game bài, game nhanh,…

- Bước 2: Nhấn vào nhà cung cấp, sau đó di chuyển đến giao diện trò chơi, tìm hiểu quy luật và bắt đầu giải trí hấp dẫn, nhận thưởng khủng.

- Bước 3: Nhận tiền thắng siêu đỉnh từ hệ thống khi đáp ứng đủ điều kiện thắng theo quy định.

Rút tiền nhanh, minh mạch về tài khoản

Tiền thắng từ quá trình cá cược, chúng tôi hỗ trợ người chơi thao tác rút tiền nhanh gọn lẹ, đơn giản theo hướng dẫn như sau:

- Bước 1: Người chơi đăng nhập vào tài khoản thành viên cần rút tiền, nhấn mục Rút.

- Bước 2: Bạn chọn 1 trong 2 phương thức mà DA88 cung cấp là Ngân hàng hoặc Thẻ cào. Sau đó, cung cấp thông tin, nhập số tiền cần rút theo hạn mức.

- Bước 3: Xác nhận giao dịch, nhận tiền về tài khoản siêu nhanh sau 3 – 15 phút.

DA88 là nhà cái cá cược hợp pháp, được Curacao quản lý, đảm bảo tính minh bạch trong hoạt động giải trí ăn tiền. Bên cạnh đó, DA88 còn ứng dụng công nghệ mã hoá hiện đại chuẩn SSL, hỗ trợ thành viên 24/7, và tung ra khuyến mãi hấp dẫn. Anh em đừng quên đăng ký tài khoản để không bỏ lỡ quyền lợi tuyệt vời ngay hôm nay!

Tin tức bên lề

Soi Kèo Euro 2024: Khuyến mãi khủng từ DA88 không thể bỏ lỡ

Soi kèo Euro 2024: Khuyến mãi khủng từ DA88 không thể bỏ lỡ sẽ mang [...]

Th6

DA88.IS: Cập nhật Scandal hot từ các CLB bóng đá hàng đầu

DA88 IS: Cập nhật Scandal hot từ các CLB bóng đá hàng đầu như Premier [...]

Th6

Bồ Đào Nha vs Cộng hòa Ireland 12/06: Phân tích Sâu và Dự Đoán Kèo Đỉnh Cao

Trận đấu giữa Bồ Đào Nha và Cộng hòa Ireland vào ngày 12/06/2024 lúc 01:45 [...]

Th6

Phân tích Slovakia vs Xứ Wales 10/06/2024 Lúc 01h45: Chủ nhà chiến thắng

Nhận định Slovakia vs Xứ Wales 10/06 lúc 01h45 sẽ khép lại lượt trận giao [...]

Th6

Cẩm nang bí quyết soi kèo tài xỉu chuẩn nhất tại DA88

Kèo tài xỉu không bao giờ là trận cược may rủi khi bạn biết cách. [...]

Th6

Cách tính kèo xiên bóng đá dễ hiểu nhất cho người mới chơi

Kèo xiên bóng đá là một khái niệm không còn xa lạ với những người [...]

Th6

Kèo chấp bóng đá: Kiến thức cần thiết cho người mới bắt đầu

Kèo chấp bóng đá là một kiến thức quan trọng khi tham gia cá cược [...]

Th6

Soi kèo Đan Mạch vs Na Uy 00h30 ngày 09/06 mới nhất

Đan Mạch đối đầu Na Uy lúc 00h30 ngày 9/6 giao hữu đội tuyển quốc [...]

Th6

Trận đấu Bỉ vs Luxembourg 09/06/2024 Lúc 01h00: Chuẩn bị tinh thần tốt

Nhận định Bỉ vs Luxembourg 09/06 lúc 01h00 khép lại lượt trận giao hữu chất [...]

Th6

Soi kèo Đan Mạch vs Thụy Điển 00h00 ngày 06/06: Đại chiến Bắc Âu

Đan Mạch đối đầu Thụy Điển lúc 0h00 ngày 6/6 giao hữu đội tuyển quốc [...]

Th6

Nhận định Hà Lan vs Canada ngày 07/ 06 – Trận giao hữu quốc tế

Cùng trải nghiệm soi kèo cá cược Hà Lan vs Canada – cơ hội lớn [...]

Th6

Chủ nhà hết hy vọng: Singapore vs Hàn Quốc 19h00 ngày 06/06

Singapore vs Hàn Quốc sẽ có màn so tài vô cùng hấp dẫn và kịch [...]

Th6